Developing practical anticipatory innovation governance

Piret Tõnurist, Project Manager for systems thinking and anticipatory innovation governance at the OECD speaks to eolas about anticipatory innovation guidance and the OECD’s work with the Irish Government to implement this guidance.

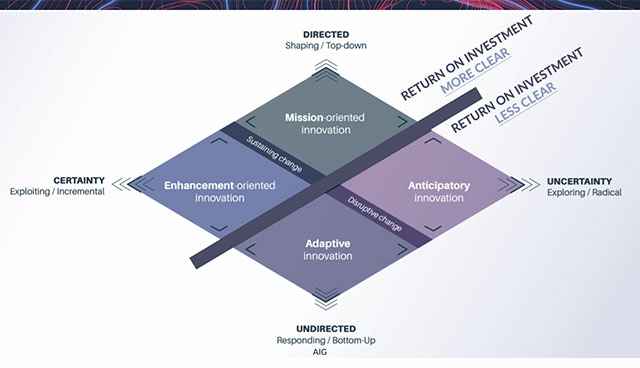

Tõnurist begins by outlining the work that she and her staff undertake as part of the OECD and how anticipatory innovation governance works: “We look at four different purposes and goals: one of those is of course to meet those goals without emissions, we want a clean transition to prevent climate change, so we have mission-oriented innovation in place. Innovation is actually serving the purpose of those results and outcomes.

“Secondly, we are of course governors of public money. We have to do our best with money that is entrusted to us, so we need to continuously innovate and enhance our system by investing in enhancement-oriented innovation.

“We also need to adapt to changing circumstances such as environmental change and citizens’ needs. We need adaptive innovation. Of course, during the Covid period this has been absolutely crucial in terms of surviving the pandemic, a rapidly developing situation where you continuously need to innovate based on new needs and new situations.

“Last, but not least, you need to have anticipatory innovation. Governments have to, by design, look at the future and the see the risks and transformational opportunities upcoming and seize them and also counter negative potential scenarios before they become a reality. Essentially, these are the core goals of a government and innovation is there to contribute to those goals. You have to have a systematic portfolio to work across these different goals and different types of innovation.”

The project manager admits that anticipatory innovation is a difficult topic to uphold in both the public and private sectors, due to day-to-day business and current needs tending to override innovation and planning. However, she warns that the world must develop a future-oriented perspective, moving from reactive governments dealing in “end-of-pipe solutions, wait-and-see positions”, to a model of proactive government that looks to achieve and shape the future.

“Anticipation is an act that is really simple,” she says. “It is essentially using futures and foresight perspectives and different scenarios to create knowledge about what is upcoming, potentially upcoming, plausible, and possible. Not only that, but also taking a decision based on that. Anticipation means deciding to do something based on the future perspective. For example, we can have forecasts about how rainy it will be in Dublin tomorrow, but anticipation is about deciding whether or not you take an umbrella with you to work.”

Tõnurist reasons that to make this happen governance that does this work is needed, to not only concentrate on the status quo but future challenges that will not only benefit the public sector, but Ireland as a whole.

“This very closely links to strategic foresight, which is a collective intelligence approach that looks at different possible futures but is also a structured participatory inclusive and impactful process when applied, based on the correct methods looking at medium- to long-term futures,” she expands. Using the large foresight exercises held in Japan as a positive example of how to generate expert knowledge of the future and generate decisions for governments to take, she says: “If we had looked at the field of social welfare or healthcare five or seven years in advance, the right stress test exercise would have been whether or not policies upheld in a situation of a pandemic.”

The OECD published an overview of strategic foresight exercises and insights, but Tõnurist says that what tends to happen is governments engaging with the insights but not applying them practically. She points to risk assessment frameworks such as that of Sweden, where the risks were described but the framework has never been implemented in terms of stress testing policies, which meant that preparedness for foreseen futures such as Covid-19 were never implemented, meaning policy structures were not resilient to those risks. Finland is mentioned as a good example of applying strategic foresight, with its model said to have “various aspects and roles of different government bodies on how strategic foresight can be applied”.

Turning to Ireland as her conclusion, Tõnurist explains the OECD’s work with the Irish Government, due to run from autumn 2021 to spring 2023: “What we found was a limited foresight experience, timescale issues and very practical issues in policy design in using innovation in the policy process. The key to closing that gap is to give license to your civil servants and to authorise an environment in terms of pursuing anticipation in practice as well.”

Alongside work to build an anticipatory governance model in Finland and a study of the future of the Slovenian public sector, Tõnurist says that the OECD is examining issues such as how to ensure that this work carries across the differing policy cycles democratic societies experience upon the election of new governments. She poses some key questions for anticipatory government in the public sector more broadly from lessons learnt elsewhere: “We have to look at different elements of the system and how we create the future in terms of citizens and participation, how we allocate budgets and resources, for example, are they only based on cost-benefit analysis, or do we also consider other scenarios in terms of input? Is experimentation allowed in your organisation to grasp those transformative changes? What kind of individual skills and capacities are you building up in your public service so different teams can uptake this work?”

Concluding, she lays out the OECD’s plans for collaboration with Ireland: “We have looked and developed an understanding of how strategic foresight works in Ireland. We talked to many different partners and encountered a lot of enthusiasm around this topic.

“From the autumn 2021 onwards until spring 2023 we’re going to look at two different things: the policy development framework, developing an anticipatory toolkit; and developing an action plan on how to integrate strategic foresight within the public service and a full curriculum for all levels of government about what kind of skills are needed for Irish governments to take up this work in practice.”