Revolutionary year: 1920 centenaries

While the proposed Decade of Centenaries commemoration of the Dublin Metropolitan Police and the Royal Irish Constabulary has been ‘deferred’, 2020 encompasses a number of significant centenaries from Ireland’s revolutionary period. How the State commemorates these events is likely to come under intense scrutiny.

Memory and history are not synonymous. Memory is selective while history is an acceptance of facts from the past, regardless how uncomfortable they may be when examined through a modern lens. Together, they are uneasy companions. Meanwhile, in the public consciousness, what is remembered is as important as what is forgotten.

The act of remembrance is often a tool of contemporary ideology or political expedience. It is here we see the greatest challenge to academic history: opportunistic public remembrance, selective amnesia and the transmission of half-truth.

However, not all events are conducive to such an end and — where it is not possible to conveniently forget or ‘disremember’ – there is potential for discord. For instance, the centenaries of a number of watershed moments from the revolutionary period in 1920 do not easily lend themselves to the post-conflict narrative of reconciliation in the Ireland of 2020.

The Black and Tans arrive in Ireland 25 March 1920 Lloyd George’s post-WWI Liberal-Conservative coalition government refused to recognise the legitimacy of Dáil Éireann or the IRA. As such, “the Irish job”, as Lloyd George referred to his government’s counterinsurgency war, “was a policeman’s job supported by the military and not vice versa”. However, with the republican campaign taking its toll, depleting Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) numbers vacated vulnerable rural barracks and coalesced instead around fortified urban stations. By late 1919, the RIC was unable to effectively counter the IRA threat and the British Government augmented its numbers by recruiting ex-soldiers. Uniform shortages forced the adoption of a combination of dark bottle green police clothing and khaki military surplus: the Black and Tans were born. Recruited from across the UK, the first Black and Tans arrived in Ireland in March 1920 and were sworn in as RIC constables. In the words of former auxiliary policeman Douglas Duff, they were “mercenary soldiers fighting for our pay, not patriots willing and anxious to die for our country”. Ultimately, militarisation of the RIC failed and, with their reputation for drunkenness, indiscipline and indiscriminate violence, the Black and Tans became synonymous with British repression in that period. |

|

Sinn Féin Lord Mayor of Cork Terence MacSwiney dies on hunger strike 25 October 1920 Terence MacSwiney was the Sinn Féin Lord Mayor of Cork and playwright who died on hunger strike in Brixton Prison, London in October 1920. Though a communication failure meant that MacSwiney did not take part in the 1916 Easter Rising, he was interned in Frongoch camp and Reading Gaol. Later elected as TD for Mid-Cork in 1918, he became Lord Mayor following the March 1920 RIC assassination of Tomás Mac Curtain. At his inauguration he declared: “This contest on our side is not one of rivalry or vengeance, but of endurance. It is not those who can inflict the most, but those who can suffer the most, who will conquer.” In August 1920, MacSwiney was arrested for possession of “seditious articles and documents”, convicted and sentenced to imprisonment. In protest, he immediately embarked upon a hunger strike, gaining global attention. MacSwiney died on the 74th day of his protest. In his final days, attempts had been made by prison authorities to force-feed him. MacSwiney’s death reportedly inspired both India’s Mahatma Ghandi and Vietnam’s Ho Chi Minh. |

|

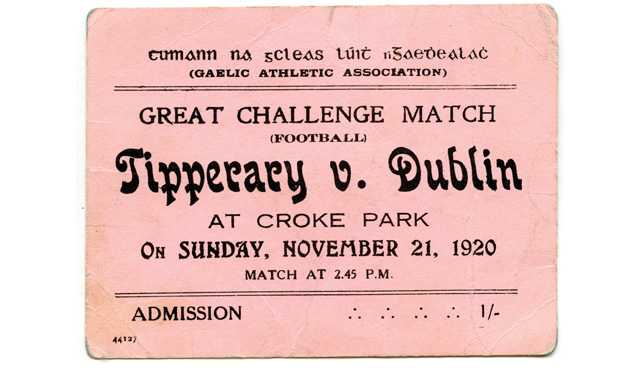

Bloody Sunday 21 November 1920 The events of Blood Sunday 1920 unfolded across 15 hours in Dublin and resulted in the deaths of 30 people. Firstly, Michael Collins’ ‘Squad’ assassinated 12 British intelligence offices and two auxiliary policemen across the city’s suburbs. Secondly, a mixed deployment of British forces killed 14 civilians, including Tipperary footballer Michael Hogan, at Croke Park. Finally, two high ranking Dublin IRA officers and another man were arrested and killed in Dublin Castle during a supposed escape attempt. It was a watershed moment that crippled Dublin Castle’s intelligence network and marked a tonal change in the war. |

|

The Kilmichael Ambush 28 November 1920 A flying column drawn from the Third West Cork Brigade of the IRA was mobilised by Tom Barry for a major ambush on the RIC’s Auxiliary Division. Deployed into West Cork the previous month, they were based at Macroom Castle and had already earned a reputation for aggression. The Auxiliaries made a routine of using the Macroom-Dunmanway road that passed through the townland of Kilmichael. The ambush position chosen by Barry ensured that it would be a fight to the death. In the end, two lorries carrying 18 Auxiliaries were halted and all but one of the occupants killed. While it had lost three men, the Kilmichael Ambush was one of the IRA’s most successful actions of the War, both militarily and psychologically. |

The Burning of Cork 11–12 December 1920 In the aftermath of the Kilmichael Ambush, Cork city was shrouded in a sense of foreboding. On 10 December, the British authorities had declared Martial Law for counties Cork, Kerry, Limerick and Tipperary and a military curfew was imposed on the city. The following day, during an ambush at Dillions Cross, an Auxiliary policeman was killed and 11 wounded with no IRA killed. In the immediate aftermath, a contingent of Auxiliaries and soldiers organised and set out from Victoria Barracks, proceeding to maraud through the city, attacking civilians while looting, burning and detonating incendiary bombs as they went. By the following day, 40 business premises and 300 residential properties were destroyed. In addition, some 2,000 people were left jobless. Firemen later testified that they were hindered by gunfire (four were treated for bullet wounds) while soldiers and policemen sabotaged firefighting equipment. The City Hall, municipal offices and Carnegie Free Library were destroyed and the total cost of destruction was estimated at £3 million (today’s equivalent of around £135 million according to the Bank of England’s inflation calculator). |