European electricity market reform

As the European Union seeks to reform the electricity market, Eurelectric’s Savannah Altvater discusses the critical components she believes must underpin market design fit for net zero.

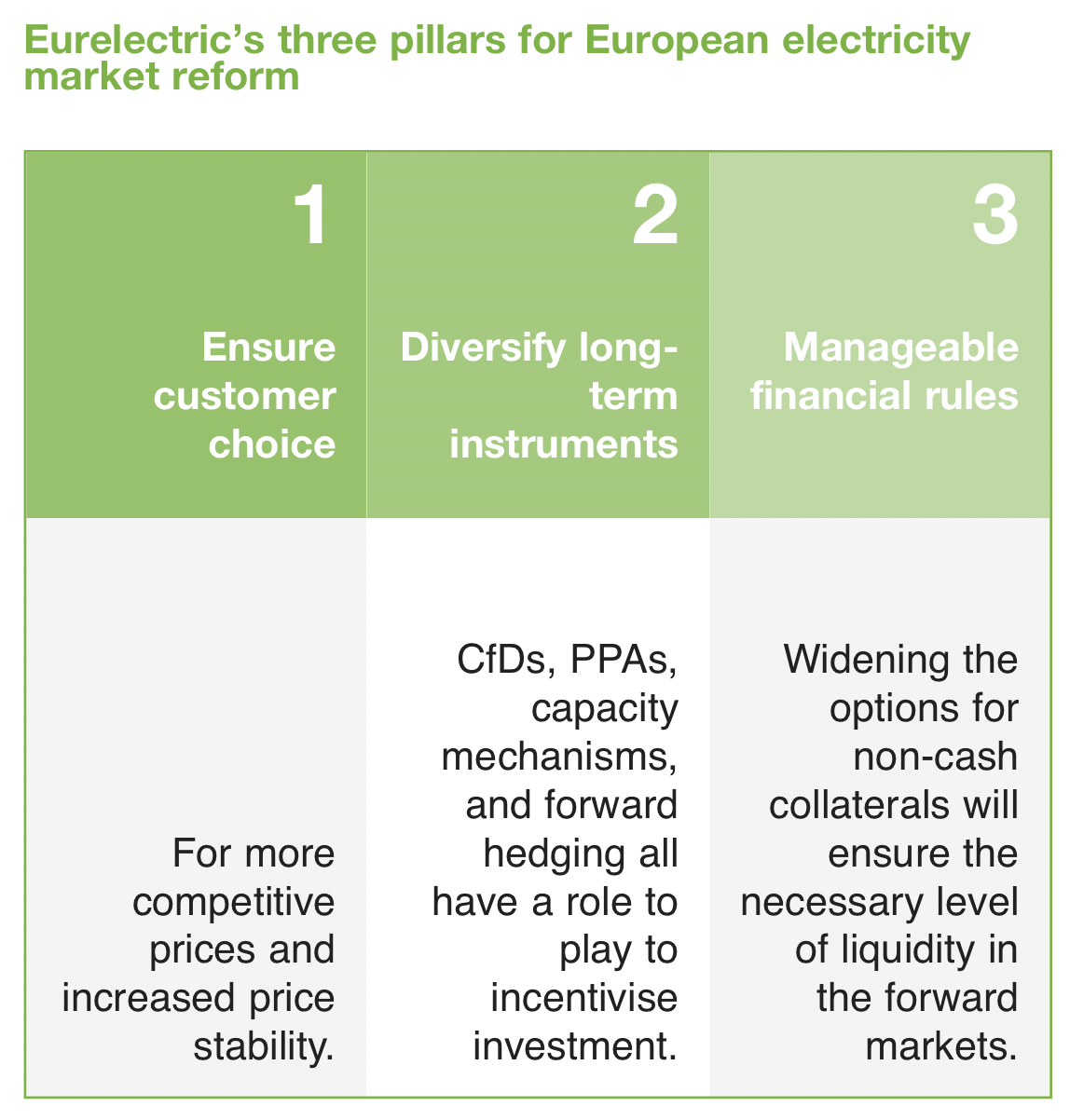

Eurelectric believes that electricity market reform must be underpinned by three critical components in the shape of ensuring consumer choice; diversifying long-term instruments; and delivering manageable financial rules.

Eurelectric is an EU-level trade association representing over 3,500 utilities across 31 countries and is currently involved in lobbying the European co-legislators to help shape reform proposals currently under negotiation.

Reform of the electricity market is the EU’s long-term response to the energy crisis experienced in 2022 and amends electricity regulations and directives set out in 2018 and 2019.

Implementation of the Clean Energy Package, finalised in 2019, was severely disrupted by the Covid-19 pandemic and price spikes in the gas market as a result of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. This led to a recognition that not enough implementation of the existing market reform had taken place to protect consumers from volatility in the market.

“Unexpectedly higher bills, supplier failures, and supplier inability to offer competitive fixed contracts left consumers in a tight spot,” explains Altvater.

The EU’s marginal price structure means that the most expensive technology sets the price. Electricity prices tracked gas price spikes and short-term markets were exposed to extreme price fluctuations, particularly for imported fossil fuels.

Altvater explains that the situation exposed the need for liquidity in forward markets to guard against these massive market fluctuations and hedge against spot market fluctuations.

In response to the energy crisis, member states delivered a diversity of emergency measures ranging from clawback mechanisms to price caps. As well as fragmenting the internal market and ultimately increasing prices for the consumer, Altvater believes that these measures breached investors’ confidence and created real disincentives for investment.

“Inframarginal price caps failed to deliver expected revenue in member states and hindered the market,” she explains, highlighting a 53 per cent decrease in the Iberian forward market between 2021 and 2022, as well as a 75 per cent drop in the signing of utility power purchase agreements (PPAs).

Altvater believes that a central component of ensuring market design is fit for the energy transition is increasing consumer choice to shield against excessive volatility.

“Rather than seeking to decouple gas and electricity, a structural reform should provide customers with a better choice of products,” she states.

Giving consumers better access to long-term pricing and supply offers, enabling them to decide on their exposure to spot prices, can be done by removing existing barriers to long-term contracts, promoting the standardisation and transparency of PPAs, and reducing credit risk on those PPAs, Altvater says.

To guard against the privatisation of profits but socialisation of losses, Eurelectric advocates for more stringent financial robustness checks to ensure only reliable retailers remain on the market.

To this end, Altvater says that Eurelectric is opposed to the Commission’s proposal for obligatory hedging requirements to be in place.

“The challenge with obligatory hedging requirements is you can lock in high prices if the hedges are put in at a certain point and suppliers are not able to unfold those hedges in a systematic way. The risk is a shortening of the forward markets because, essentially, what you have is a run on the forward contract markets at the same time to be compliant with these obligations.

“There is a need to strike the right balance between consumer protection and supply regulation in order to preserve competition and we believe that stress tests are a better mechanism than obligations.”

Long-term investment signals

A second key component of market reform raised by Altvater is that long-term investment signals are key for the build-out and mitigating price volatility.

Describing the investment needs for renewable energy across the EU by 2030 as “colossal”, Altvater highlights the need for over 700GW of new capacity, the renewal of existing capacity, build out of storage, and demand response.

“To keep adequate hedging in the forward market we need to enhance liquidity by removing barriers, one of which is the long-term transmission rates. Currently, TSOs only generally offer long-term transmission rights (LTTRs) for a one-year interval and we are asking for an extension to longer timeframes to enhance the liquidity and then consider voluntary market making,” she says.

Altvater believes that Contracts for Difference (CfDs) can serve as a complement to market-based investments but warns that retroactive changes should be avoided, only applying to new build and deep retrofits of existing power plants where necessary.

Additionally, she says: “We should consider implications on forward markets and public budgets. When we talk about measures to support consumers that come from the State budget, we talk about moving the cost from the energy bill to the tax bill and this is something we also have to take into consideration when it comes to CfDs.

The devil is in the detail when it comes to the design and use of CfDs. They are just one tool in the toolbox and therefore should be voluntary, not mandatory. There is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ CfD and so adequate design and contractual innovation matter.

“Given that a massive use of CfDs would create challenges for investment signals and forward market liquidity, our position is that CfD use should be strategic and sparing.”

Turning to capacity mechanism, Altvater wants to see these become a more integral and integrated part of the market design.

Pointing to the long lead-in time for capacity mechanisms to be approved and then implemented by member states, she says: “We are looking for these to become a permanent part of the market design, so that energy companies know that they can count on this in the long term. Then, of course, we must ensure technological neutrality and include all kinds of energy sources, as well as flexibility.”

In October 2023, the Council reached an agreement on the electricity market design (EMD), enabling the beginning of negotiations with the European Parliament. With European elections scheduled for June 2024, Altvater points out the need for urgency to have the reform finalised, signed, and published no later than April 2024, with implementation likely to take around one year on average for member states to transpose the changes.