National Children’s Hospital: Costs risks remain

Risks still remain that the cost of the National Children’s Hospital project could increase further beyond the estimated €1.73 billion Capital Investment Requirement, the independent review of escalation in costs of the project by PwC has outlined.

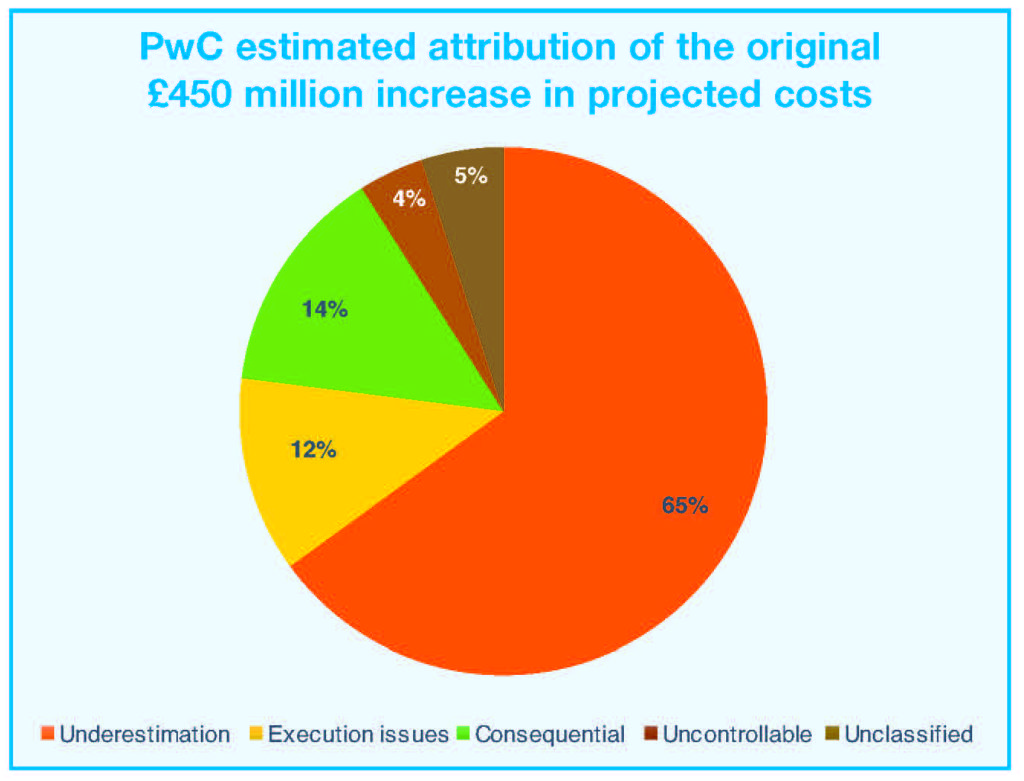

Identified in the Definitive Business Case of April 2017 with a total cost of €983 million, the National Paediatric Hospital (NPH) Project has been the focus of intense scrutiny after it was revealed that costs had spiralled by some €450 million to €1.43 billion.

However, it now appears likely that further costs will be incurred, raising even further the potential overall cost of the project. The PwC review has identified the potential further requirement of some €293 million for the likes of integration of the three existing hospitals (€86 million), IT systems (€97 million), electronic health record implementation (€52 million) and a research and innovation centre (€18 million). A new figure of €1.73 billion also included the provision of €40 million for costs already occurred in relation to the Mater site.

Even following the conclusion of the Guaranteed Maximum Price (GMP) process, there are further risks to cost inflation above and beyond the €1.73 billion figure. Identified by PwC, key risks include the fact that elements of the design remain to be finalised in the agreed packages of work assumed for the main construction phase. Similarly, elements of the design remain to be fully quoted and costed. The €50 million sum approximated within the BMP may not be adequate.

Additionally, the current contract contains exclusions to allow for the recovery of costs relating to tender price inflation above 4 per cent, as well as cost increases arising from statutory changes such as VAT increases. One significant factor is the current pay claim from unions representing the construction sector for a 12 per cent pay increase. The contract would allow construction firm BAM to pass on construction inflation.

These costings are based on the assumption that the project will meet the 2023 schedule of delivery, however, any slippage on the target date would result in delay costs. The PwC report identifies significant weakness in governance controls across the project and potential future costs exist if these controls are not addressed and rectified.

Value for money

Notably, the terms of reference given to PwC did not include a requirement to assess whether the inflated cost of the hospital project represented value for money. The findings of the critical report centred on significant failures occurring during the planning and budgeting stages of the project; a poorly coordinated and controlled GMP process and insufficient scepticism and challenge.

On the two-stage procurement process used to award the construction contract, a widely used approach, the report states that in this instance “necessary controls required to mitigate the associated risks and consequences of this approach were not put in place”.

In addition, the report describes as “poor” the understanding of the risk profile associated with the procurement and contracting strategy at all levels of the governance structure. As a result, the capital budget made no provision for the price premium the public sector would have to pay the contractors to bear the risks transferred to them through the GMP process. Contingency to absorb risks during the agreement of a GMP were also not factored into the capital budget and as a result, the budget “significantly underestimated” the likely outturn cost.

While the procurement strategy did include a mitigation option to switch contractor if a GMP could not be agreed, the report’s authors describe this as an “unrealistic option”, highlighting the likelihood that such a move would increase delay and cost further.

A further criticism of the early stages of the project is that the Definitive Business Case (DBC), on which the investment was based, contained “material errors” and did not adhere to the Public Spending Code. The reports state that the DBC “overstated the maturity of the project and level of confidence in the forecasts, and understated the complexity and risks”.

This invariably “impaired” the ability of stakeholders to provide effective challenge. Considerable gaps were identified in the Project Execution Plan (PEP), outlined as key controls being identified and not defined. This led to the project progressing without proper control arrangements.

Execution

Imbalance between the hospital and BAM was created by the initial process combined with limited direct engagement by the NPH Executive in the latter stages “restricted their influence” on the settlement with BAM.

The report also found that the project’s quantity surveyor, Linesight, used a number of different techniques to determine quantities than those of the contractors. For example, contractors estimated that the hospital would need more than double the length of pipes than was estimated by Linesight. This, coupled with “fragmented” cost trend reporting, made it difficult to interpret and put it at risk of error. As a result, the NPH Executive and the NPHDB failed to see the unfolding picture of rising costs.

Describing cost trend reporting across the project as generally “unstructured, fragmented and lacking key information”, the report adds that the processes to manage risk, change and documentation were ineffective, while project systems were “insufficient”.

It adds that the commercial construct of the Design Team (firms of architects, design engineers and quantity surveyors), created accountability gaps and impaired the effective coordination of the GMP Process.

Governance

Too much trust by the NPHDB being placed in the NPH Executive and Design Team led to insufficient challenge and scepticism. This environment allowed progress to happen too quickly without rigorous challenge. In addition, there was an “overreliance” on written answers by the Design Team in relation to cost certainty at the tender stage. The report suggests that evidence exists that should have prompted earlier and greater challenge by both the NPHDB and the NPH Executive.

Pointing to a “limited” experience around specific healthcare infrastructure development within these two bodies, the report highlights a reliance on the expertise of the Design Team, making effective oversight challenging.

It concludes that delays in the design development process and the costing of packages led to critical information only being visible in the latter stages of the GMP Process, meaning the governance structures became reactive “with virtually no leverage to influence the outcome”.

Recommendations summary

- project control environment should be overhauled to bring it up to the level of maturity and sophistication required for a project of the scale, complexity and importance of the NPH Project;

- comprehensive plans to mitigate the residual risks identified;

- a Project Assurance Strategy, should be developed and implemented for the remainder of the NPH Project;

- the commercial capability and capacity of the NPH Executive should be strengthened so that it is more self-sufficient and less reliant on external advisors;

- the Executive of the NPH should be strengthened in the short term to support the planning and execution of the next phase;

- consideration should be given to opportunities for the closer working of the NHPDB and the CHI Board, including the potential for some shared appointments to promote integration and to address skills gaps;

- the NHPDB should request confirmation of a number of key decisions in relation to procurement/approach for medical equipment, ICT and electronic health records to enable effective planning of the next phase of the programme;

- the scope and responsibilities of the advisory firms that constitute the Design Team should be reviewed to reflect their future roles;

- in view of the potential consequential programme risks, a scrutiny process that includes all levels of the governance structure should be put in place.

Other capital infrastructure projects

- the rules that govern public sector spending on major capital projects should be strengthened. The standards to which business cases must adhere should be more clearly defined and robustly enforced; and

- a central assurance and challenge function should be established within Government to provide consistent challenge to and review of major projects throughout their lifecycles.