Irish competitiveness buoyant

Ireland has been ranked in the top 25 of three major global competitiveness indicators, compiled by the World Bank, the World Economic Forum (WEF) and the International Institute for Business Development (IMD).

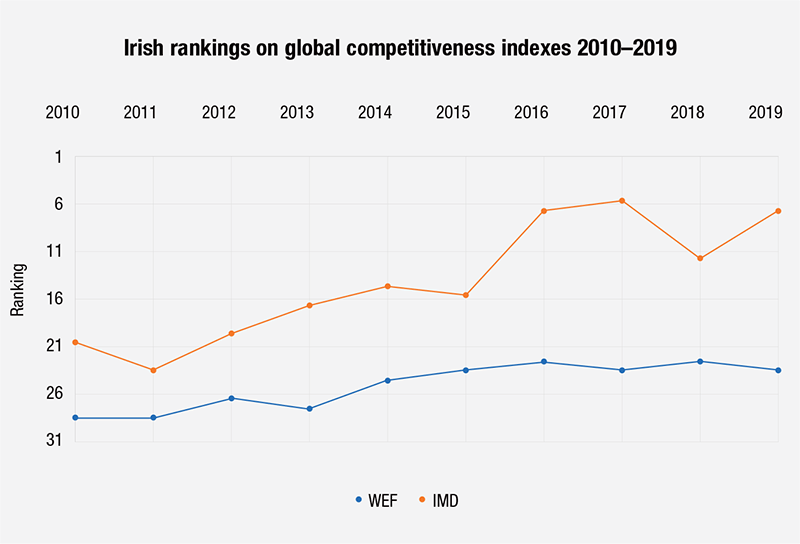

Ireland was ranked seventh out of 63 in the IMD’s rankings, a significant improvement given that the country had begun to slide down global competitiveness ratings in the late 2000s and early 2010s before recovering in the middle of the latter decade. Ireland had ranked as low as 24th in 2011 and as high as sixth in 2017.

The WEF’s Global Competitiveness Report 2019 ranked Ireland at 24th out of 141 countries, one space down from its position in 2018, but still higher than the start of the 2010s, where the country ranked 29th. In the breakdown of index components, Ireland ranked in the top 10 globally for: social capital; conflict of interest regulation; energy efficiency regulation; electricity access; debt dynamics (joint first in the world with 33 other countries); school life expectancy; trade tariffs; reliance on professional management; ratio of wage and salaried female workers to male workers; credit gap (joint first with 97 other countries); and cost of starting a business. Ireland’s worst rankings were non-performing loans (116th in the world), terrorism incidence (94th), mobile-cellular telephone subscriptions (97th), competition in services (97th), complexity of tariffs (113th) and soundness of banks (98th).

The National Competitiveness Council (NCC) define competitiveness as “the ability of enterprises to compete successfully in international markets” in its report, Ireland’s Competitiveness Challenge 2019. Two of the main criteria of competitiveness are productivity and factor costs; productivity being in line with the cost base is what defines a competitive economy. If prices are too high relative to productivity, then domestic businesses find it hard to export goods and services and foreign business will have no incentive to locate with such an economy.

The NCC report states that Ireland’s Harmonised Competitiveness Indicator shows three broad trends since the turn of the century: substantial loss of cost competitiveness between 2000 and 2008, with costs rising faster than elsewhere; substantial improvements in that regard during the crisis from 2008 until 2015; and sustained improvement ever since.

Ireland, the report says, is “particularly vulnerable to external shocks”, i.e. market-altering behaviour from abroad, due to its small and open nature as an economy, meaning that high global competitiveness rankings are “fundamentally important”. An “increasingly challenging international environment” in the era of Brexit and heightening trade tensions between the USA and China make this all the more pertinent. Indeed, Brexit and its now-familiar threats to Irish SMEs, the agri-food sector and border communities are identified as the biggest threat to Irish competitiveness within the NCC’s report. Further threats mentioned are: slower growth in the global economy; the changing international tax landscape; trade tensions worldwide; and the global effort to avert climate disaster.

The Government has committed to the NCC’s priority of growing Ireland’s productivity and competitiveness as part of the Future Jobs Ireland 2019 plan. The Government had agreed to respond to the publication of Ireland’s Competitiveness Challenge within two months, although it is unclear how February’s election will affect that timeframe. The report warns that the concentrated nature of the Irish economy means that the underperformance of a small number of firms, sectors or external markets “could have a wider impact on the Irish economy”.

The NCC cites the examples of pharmaceuticals and chemicals and computer services, which accounted for 60 per cent of goods exports and 43 per cent of services exports respectively in 2017. This issue is also compounded by a lack of diversity in destinations for goods exports: over a quarter of all goods exports from Ireland go to the USA and 11 per cent go to the UK. The NCC has in the past recommended the pursual of government initiatives to rebalance the economy and safeguard against external factors by improving the productivity in the less productive sectors and firms.

The Competitiveness Council says that it welcomes Future Jobs Ireland 2019, but also adds that it would recommend:

- more granular productivity data in order to inform and improve the development of policy to encourage improvement in Ireland’s competitiveness;

- the implementation of a plan to intensify business research and development in order to boost productivity growth;

- the identification of measures that inhibit “investment in knowledge-based capital” and the development of plans and measures to overcome this; and

- the development of policies to improve firm management, which is inextricably linked to firm production.

The NCC also warns that the high levels of government debt that Ireland is currently experiencing (sixth highest in the OECD) would make it difficult for the Government to boost economic growth in the event of a slowdown. It concurs with the Irish Fiscal Advisory Council’s position that the debt should be paid down now and the reliance on corporation tax to fund spending should be tapered in order to give the Government a more predictable tax base.

The report also features specific recommendations in the six sections that the NCC chose to focus on: digital economy; infrastructure; productivity, skills and education; cost of credit; legal service costs; and general liability insurance costs.

Key recommendations of Ireland’s Competitiveness Challenge 2019

Digital economy:

Finalise and publish the New Digital Strategy and the Cyber and Artificial Intelligence strategies; improve Government handling of personal data in line with the Data Sharing Act and establish the Data Governance Board; and provide public funding to SMEs to co-finance investment in digital.

Infrastructure:

Meet the Government’s commitment of increasing public spending to at least 4 per cent of GNI; expedite the publication of the Regional Spatial and Economic Strategies (RSESs) in the Northern & Western and Southern regions; and complete and publish new governance arrangements for major infrastructure projects to mitigate the risk of project overspend and the Construction Sector Productivity Assessment and Action Plan.

Productivity, skills and education:

Develop an Action Plan to deliver on the five action areas outlined in the Review of Pathways to Participation in Apprenticeship; and undertake a feasibility analysis of the international schemes outlined in the OECD paper Seven Questions about Apprenticeships to incentivise employers to recruit apprentices from consortia led apprenticeship programmes.

Cost of credit:

Explore options to broaden the Strategic Banking Corporation of Ireland’s on-lending partners; and research and address the factors causing higher SME interest rates in Ireland relative to the euro area on SME loans.

Legal services costs:

Publish the Services Producer Price Index with a more detailed sector breakdown; and ensure that the Legal Services Regulatory Authority is sufficiently resourced to expedite the delivery of its work program.

General liability insurance:

Explore legislative options to compel insurance companies to provide claims data; and publish a report setting out key information on employer liability and public liability insurance claims.