How we value work

As the pandemic exposes just how vulnerable employment can be across multiple sectors in Ireland, a 2020 NESC report examines how we value work and how that value has been changed by what Covid-19 has done to our employment landscape.

“The crisis has brought into view the occupations and work that are seen as essential and critical to the wellbeing of the nation and in doing so, has brought attention to the wages and terms and conditions of workers in those areas,” the report, How we value work: The impact of Covid-19 by the National Economic and Social Council (NESC), says.

Published in June 2020, the report states that by the end of April 2020, the adjusted measure of unemployment stood at over 694,000, an unemployment rate of 28.2 per cent, and that almost half the population have had their employment situation affected by the pandemic. “Employment vulnerability and job quality have moved from the periphery to centre stage in economic and enterprise policy, magnifying the importance and need to understand and indeed re-consider what good jobs mean today, and into the future,” it says, going on to note that it is those on the lowest wages who have to travel to work who have been placed at the highest levels of risk.

While the report states that health and safety are paramount, it also says that “the nature of income, terms and conditions had come to define the quality of employment, or a good job” and that “the pandemic has reemphasised the pre-existing negative aspects of some poor jobs” and “has reinforced the importance of adequate wages and hours”.

Using various examples, the report begs the question of whether or not those on ‘if and when’/zero-hour contracts whose work has been especially affected by the pandemic should be entitled to pandemic unemployment payments. Other examples offered of those in work exposed to danger by the pandemic include: carers who have insufficient hours of work in one workplace, and who may then also work in other care settings; workers on low pay who are more likely to live in over-crowded accommodation; and workers with poor sick-pay provisions, “who rely on State illness benefit which until recently only commenced on day seven of an illness, and at €203 weekly maximum”.

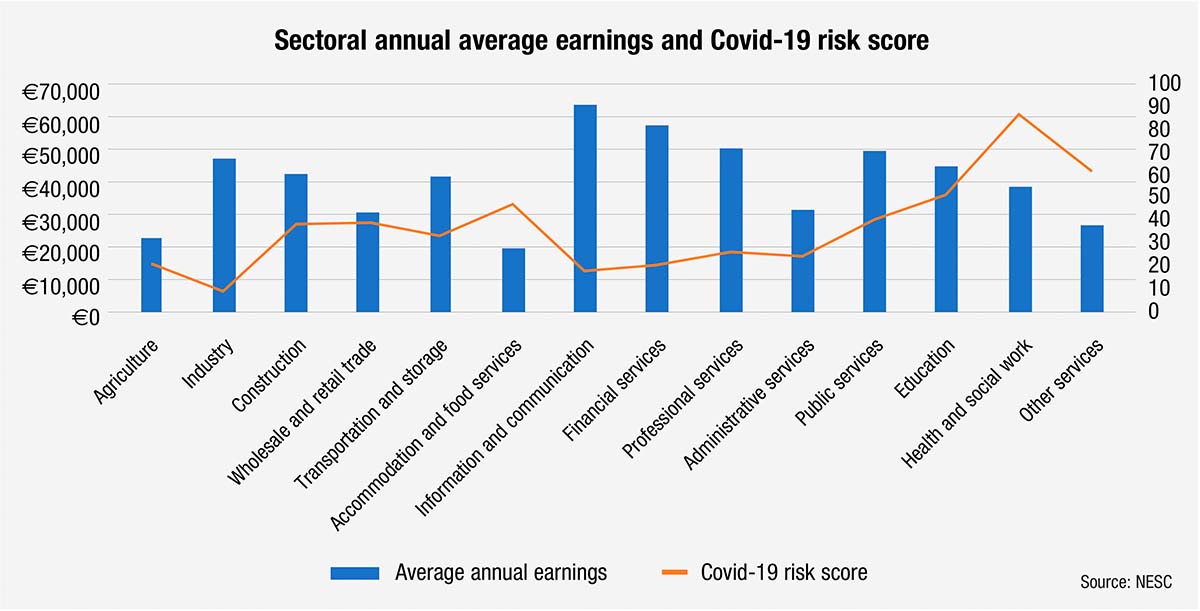

Using a series of considerations, NESC then calculates a Covid-19 risk score based on a given sector. One such factor is contact intensity, where it is noted that there are around 864,000 people in Ireland in occupations that require “very close physical proximity to other people”, a rate of 37 per cent of all workers. Such occupations include barbers/hairstylists and food and beverage preparation and service workers. Occupations such as graphic and web designers, marketing and sales, business services (finance, sales, strategy, HR, accounting), software development, architects, media, and writing and content provision are said to be occupations with low contact-intensity and lower Covid-19 risk scores due to their lack of contact with the public. It is also noted within the report that it is “questionable how long this factor will remain an important one”, and with the comprehensive rollout of vaccines among the adult population in Ireland since the report’s publication, the risk here will have been significantly lowered.

The pandemic has also seen sectors that were seen as being under threat, such as food-retail, food-delivery and couriers/transport, redefined as essential and ‘front-line’, protected to an extent from rapid unemployment, leading to the Government issuing sectoral guidance as to what constitutes essential work. The report states: “On one hand, employment and incomes have been maintained in these occupations during the crisis, which speaks to the resilience and quality of these jobs. On the other hand, some workers in the short-term may not be as attracted to these occupations given that they continue to be active even in the face of a pandemic.”

The ability to work from home has also become a quantifier of a job’s quality due to the pandemic, the report states. Of those whose employment has been impacted by the pandemic in Ireland, 34 per cent have started remote working from home. In broad terms, these are sectors where remote working and digital technology can be used and as such are somewhat protected from an unemployment shock as work has been able to continue interrupted and these sectors are also best placed to restart earlier than others (e.g., financial services, professional and business services, ICT sector, and parts of manufacturing). Such occupations account for roughly 945,000 workers across sectors in Ireland, while around 1.15 million workers in Ireland are in occupations where working from home is more difficult, such as education and health services, construction, wholesale and retail, transportation and utilities, agriculture, leisure, and hospitality.

“One immediately obvious lesson from the crisis is that it has made good jobs better and more valuable to workers, and poor jobs worse but more valuable to society,” the report states, a contention which becomes evident when viewing the contrast between sectors with higher incomes/lower risk, and those with lower incomes/higher risk: 670,100 workers in ICT, financial and professional services, and wider industry have average annual incomes of around €55,200, and an average mean risk score for Covid-19 of 10.6. while 902,400 workers in retail, hospitality, healthcare, and other services (e.g., hairdressing, security) earn €29,300 on average per annum, and have a mean Covid-19 risk score of 57.6.

By May 16, 2020, 31 per cent of the 24,036 confirmed cases of Covid-19 in Ireland, 7,615 in total, were among healthcare workers despite the fact that they make up just 12.5 per cent of the Irish workforce. With an average income €25,000 lower per annum than workers in the ICT sector, healthcare workers had a risk of infection seven times greater than those in ICT.

The report concludes: “The Covid-19 emergency has brought new vulnerabilities to light and re-emphasised some pre-existing ones. It has forced a reappraisal of what are termed good jobs and how work is valued… Policymakers must take the opportunity now to consider how the coincidence of those pre-existing issues and new criteria inform our understanding of the quality or value of work. The arrival of the pandemic has knocked society’s approach to how work is valued: what jobs are essential, frontline, or involve workers putting themselves at risk in the service of others? There is a stark contrast between sectors with higher incomes/lower risk, and those with lower incomes/higher risk. Covid-19 has made good jobs better and more valuable to the worker; and made poor jobs worse, yet more valuable to society. This has consequences for workers, employers, and policymakers.”