Bringing the past to life at the National Archives Treaty exhibition

Meadhbh Monahan looks at the National Archives’ Anglo-Irish Treaty exhibition, launched 90 years after its signing, and discusses its significance with archivist Elizabeth McEvoy.

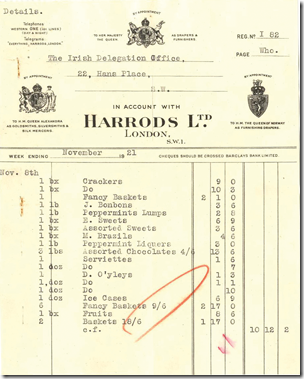

An invoice for Harrods totalling £14 13s 1½d for items such as bon bons, fruit baskets and peppermint lumps is among the array of bureaucratic and “sometimes byzantine” records contained in the National Archives’ online ‘Treaty’ exhibition.

Indeed, the meticulous recording of expenses for the journeys to and from England and the money spent on transport and accommodation is particularly relevant in today’s economic climate, according to archivist Elizabeth McEvoy.

“This fiscal rectitude is important given the economic situation the country now finds itself in. Michael Collins as Minister for Finance would have been particularly concerned about this,” she notes.

The records show that Collins received a critical advance loan of £50 to cover his expenses in travelling to England, remarking that: “I have about £3 in my pocket. It would be serious if I could not give a porter a tip in Holyhead.”

McEvoy is keen to justify the Irish delegation’s spending while transacting the treaty deal e.g. hiring Rolls-Royces and staying at Hans Place in Knightsbridge.

“We felt it was very important that people did not get the wrong impression that they sat around and ate sweets and lived it up at the expense of this fledgling state.”

The British delegation were “formidable negotiators” and it was essential that the Irish delegation were seen as “diplomatic equals,” she tells eolas.

The British delegation were “formidable negotiators” and it was essential that the Irish delegation were seen as “diplomatic equals,” she tells eolas.

The Harrods receipt “shows the human angle” to the fraught negotiations that lead to the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty and, ultimately, to the bloody Irish Civil War.

Launched to coincide with the 90th anniversary of that seminal moment in the nation’s history, the online exhibition was the brainchild of the National Archives. That body felt that, with the development of digital humanities (the integration of computer technology into scholarly activities), it was time to make the documents available “at the click of a button.” A lack of permanent exhibition space for the documents furthered the archives’ impetus for the display.

The exhibition went online on 6 December and the reaction has been “overwhelmingly positive”, ranging from computer literate archive browsers to those with a passing interest in history.

Arts Minister Jimmy Deenihan, who is a former history teacher, commented: “Irrespective of your political persuasions this exhibition has no bias and no agenda. It is simply an excellent opportunity for the public to see, not only the treaty itself but the papers leading up to the signing of the treaty.”

He hoped that the exhibition will “bring to life the story of the establishment of the Irish Republic to a much wider audience than before.”

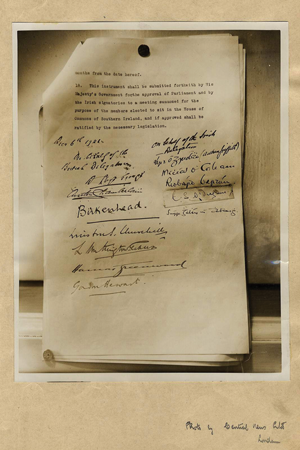

Following the travails of the Irish delegation and their British counterparts, it is hoped the exhibition will be a useful educational tool, particularly for leaving cert history students. It contains high quality images of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, a gallery of documents relating to the negotiations drawn from the Dáil Éireann archives, biographies of the Irish and British signatories and portraits by Sir John Lavery, sourced from the Hugh Lane Gallery.

Marked ‘secret’, counter-proposals from the Irish delegation show their suggestion that the oath of allegiance would read:

“I do swear to swear true faith and allegiance to the Constitution of Ireland … and to recognise the King of Great Britain as Head of the Associated States.” The final wording, which was anathema to many republicans, swore “to be faithful to H.M. King George V, his heirs and successors by law, in virtue of the common citizenship of Ireland with Great Britain and her adherence to and membership of … the British Commonwealth of Nations.”

On the issue of Ulster, a letter from Arthur Griffith to Éamon de Valera reports on a meeting between himself, Michael Collins, Austen Chamberlain and Gordon Hewart. It reads: “[Chamberlain and Hewart] argued the ethics of partition very little.” The letter outlines how the Irish delegation called for the six counties to vote in or out, with those who voted out being a subordinate legislature to the Parliament of Ireland, whereas the British delegation wanted Ulster to vote as an entity. They also suggested that the six counties would remain as they were but could come into an all-Ireland parliament at a later date.

“In the end I told them that no Irishman could discuss with his countrymen any association with the British Crown unless the essential unity of Ireland was agreed to by the decidents,” Griffith wrote.

McEvoy concludes: “We hope it will be a useful tool enabling researchers and the public to follow the inner workings of government and the decisions taken by the delegation at a crucial time in the country’s history.”

| British delegation: | |

| Prime Minister | David Lloyd George |

| Lord Privy Seal | Austen Chamberlain |

| Lord Chancellor | Lord Birkenhead |

| Secretary of State for the Colonies | Winston Churchill |

| Secretary for War | Sir Laming Worthington-Evans |

| Chief Secretary for Ireland | Sir Hamar Greenwood |

| Attorney General | Sir Gordon Hewart |

| Irish delegation: | |

| Minister for Foreign | Affairs Arthur Griffith |

| Minister for Finance | Michael Collins |

| Minister for Economic Affairs | Robert Barton |

| George Gavan Duffy (providing legal expertise) | |

| Éamonn Duggan (providing legal expertise) |

21 January 1919

21 January 1919

First session of Dáil Éireann in Mansion House

21 January 1919

Irish War of Independence begins with the killing of two Royal Irish Constabulary officers

September 1919

Dáil proclaimed an illegal body by the British authorities

March 1920

Arrival of the Black and Tans, supplemented by the Auxiliaries in August

21 November 1920

Bloody Sunday: 14 civilians, 14 British agents and three republican prisoners killed

23 December 1920

Government of Ireland Act divides Ireland into Southern and Northern Ireland

26 May 1921

British Cabinet decides that if the Southern Parliament is not in operation by 12 July, martial law will be extended from Tipperary, Limerick, Cork and Kerry, to the rest of Southern Ireland

24 June 1921

British Prime Minister David Lloyd George invites Éamon de Valera to a conference in London to explore “to the utmost the possibility of a settlement”

9 July 1921

A truce ending the War of Independence is agreed and comes into force on 11 July

12 July 1921

An Irish delegation travels to London for preliminary discussions with the Prime Minister

11 October 1921

Formal negotiations between the Irish and British delegations begin

22 November 1921

The Irish delegation demands ‘external association’ (an alternative to Canadian-style ‘dominion status’)

24 November 1921

The British response rejects any settlement which does not acknowledge some role for the Crown in Ireland

6 December 1921

The treaty is signed at 2.15am after Lloyd George delivers an ultimatum: sign or face an “an immediate and terrible war”

8 December 1921

de Valera refuses to recommend acceptance of the treaty.

Irish Cabinet decides by 4-3 to recommend the treaty to the Dáil.

7 January 1922

Treaty approved in the Dáil by 64 votes to 57

14 April 1922

Four Courts are occupied by anti-treaty forces

16 June 1922

General election: pro-treaty Sinn Féin win 58 seats while anti-treaty Sinn Féin only gain 35

28 June 1922

The first shots of the Civil War are fired as pro-treaty forces shell the Four Courts