Infinite links

Infused with his own maps and photography, Garrett Carr’s The Rule of the Land: Walking Ireland’s Border details journeys by foot and canoe along the entirety of the 499 km-long border on the island of Ireland. Through these excursions, Carr explored the nuances of what had, until recently, become an increasingly irrelevant stroke of the cartographer’s pen.

Some years ago, before the term ‘Brexit’ was conceived, I started exploring Ireland’s border. I was writing a book about the border and making maps of it. Mostly I walked but I started by canoeing the length of Carlingford Lough, making landfall at Narrow Water. From there the border climbs the Cooley Mountains and winds on for another 300 miles or so to Lough Foyle. My series of walks was completed just after the UK voted to leave the EU. The borderline route is almost entirely farmland, fir plantation or highland bog. Only rarely does it cross open country completely unmarked, it is usually hosted by something; a hedgerow, a drystone wall or a ditch for example. These dividers are not explicitly marked as international boundaries, they are impossible to distinguish from all the other ditches, walls and hedgerows around them.

I was interested in charting the borderland ecology: forests, hills and heath and charting its defensive architecture; forts, castles and checkpoints – a 2,000-year history of control. But unexpected things also caught my eye. On day two, following a border stream up into the Cooleys, I found a set of stepping stones leading to a newly built house. It was a narrow stream, only a few stones were required to make a crossing point. They might have been placed there by children. Naturally the crossing was not marked on my Ordnance Survey map, despite its close scale.

“Ireland’s border is simply not suited to constriction and the connections prove it. How can such a border be hardened successfully? The answer, one suspects, is it can’t.”

There are, officially, 208 cross-border roads. This number was arrived at recently in a joint mapping project conducted by the Department of Transport and Northern Ireland’s Department for Infrastructure. However, I can report that there are also lots of alternative routes they probably missed. Crossings like the stepping stones on the Cooley foothills would never be captured by such a survey.

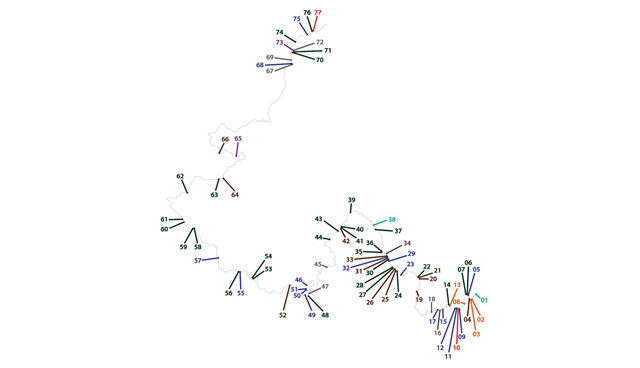

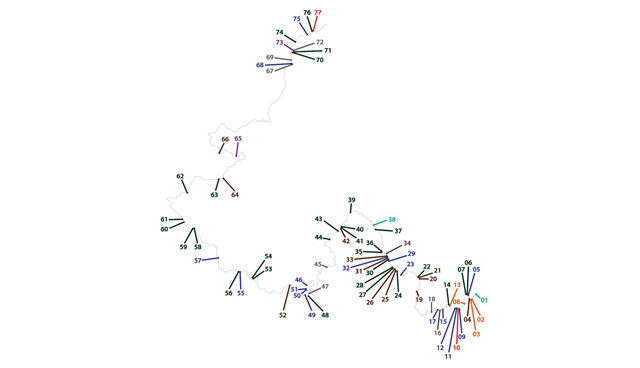

On the day I photographed the stepping stones I was not entirely sure why I found them so touching. When I had completed my survey, I had found 76 more unofficial crossings places and I had figured it out: each is a reminder of our irrepressible urge to move around our localities. The basic, human, daily stuff of life: visiting neighbours, taking short-cuts to a shop, or herding cattle from one field into another. The fact that they were not marked on any other map was part of their appeal too, some things are beyond the reach of the State.

I called these features ‘connections’. The majority were gates linking fields; a lot were small bridges, sometimes just a couple of planks wide, and some others were cut pathways. I charted them for a map called The Map of Connections, which also included a photo of each nexus. I have exhibited this map a few times around Ireland, including in the Ulster Museum, Belfast. The first edition of the map may have seemed like a rather niche creative experiment but I felt there was something optimistic about this representation of the border, showing it as open and alive; an energy fostered by the Good Friday Agreement. A few years ago, I thought this was the future direction of Ireland’s border, that it would only soften further. But now the border’s future is more unclear than it has ever been. It seems that nations everywhere are hardening their attitudes to their borders and Ireland’s is likely to harden too. This is the context in which The Map of Connections is now viewed. The map has gained a new pertinence.

Over the course of several weeks, I have used Twitter to platform my photographs of border connections. They have proven popular in Ireland and beyond, getting liked and retweeted hundreds of times. Suddenly the connections mean a lot more to a many more people. These innocuous, bucolic images of little gateways and plank bridges seem to have something to say about Brexit and Ireland. One thing I did not expect was that people would find the photos funny. They offer their own wit in comments: “If you pass me the coordinates I’ll give you 5 per cent of my courgette smuggling operation.” “You’re going to need a few square metres of wheelbarrow park when the traffic backs up.” “Does a soft Brexit mean the gate is left open and a hard one means they put a padlock on it?”

I get the joke now. There is something inherently comic about the idea that a hole in a wall between Armagh and Monaghan may fundamentally shape the way the UK exits the EU. My photos reveal the ridiculous.

By now many British citizens know that there are more crossings along Ireland’s border than along the EU’s entire eastern frontier. But I suspect an image of what the border actually looks like on the ground has still not taken common hold. So, standard go-to images of international frontiers fill the void. I think there is a general conception that borders are rooted in formidable topography. It’s true, international boundaries often correspond with mountain ranges, for example, or wide rivers. What my connection photographs show is something different; a perfectly tame, easy, interwoven and worked rural environment. Not many natural difficulties, no ravines and few mountains. In fact, the border only has one rise that could be called a mountain at all, Cuilcagh, between Fermanagh and Cavan. It is the 165th highest peak on the island of Ireland but by far the highest point of the border.

Someone commenting on Twitter, a mathematician perhaps, took issue with the way I had placed a final number, 77, on these unofficial connections. “There are far more than that,” they said, “the number is in fact infinite”. This is true, and the photographs reveal it. For example, connection 27 is just a plank over a stream. The plank gives me something to photograph, number and chart, but the stream is only about two-feet wide for a mile in both directions, easily stepped over by anyone half-agile. Most of the border is mild in this way, its geography is rarely constrictive. The fences can only constrain sheep, the walls are rarely more than four feet tall and the rivers can be paddled across.

Ireland’s border is simply not suited to constriction and the connections prove it. How can such a border be hardened successfully? The answer, one suspects, is it can’t. The entire line is a crossing place, busy with trade, encounter and possibility. I hope now that these photographs aren’t just going to become part of history, an archive of brief moment, the twenty-odd year phase between the Good Friday Agreement and the return to a border of the past.

Garrett Carr is the author of The Rule of the Land: Walking Ireland’s Border (Faber & Faber). See more of his maps at www.garrettcarr.net.