Supporting cross-border trade and collaboration during the pandemic

Aidan Gough, Designated Officer of InterTradeIreland, discusses how the organisation has responded to the Covid-19 crisis and why cross-border trade will be vital to economic recovery.

The catastrophic impact of the Covid-19 pandemic has already had a significant impact on cross-border trade and business development. This is in stark contrast to the latest figures before the crisis hit. Cross-border trade had been at an all-time high of €7.4 billion and was a big economic driver for both jurisdictions.

“Once the current crisis hit, like most organisations, our first priority was to make sure our staff were safe and that the organisation could function when the island went into lockdown. The staff have been fantastic. Just as our employees contributed to business growth during the period of expansion they’ve been working hard when SMEs need us the most,” states Aidan Gough.

InterTradeIreland initially turned its attention to the cross-border trading companies and organisations who were on its programmes. The economic development body is unlike both Enterprise Ireland and Invest Northern Ireland who have their own clients, whereas the cross-border body runs programmes that assist businesses through various initiatives. “We had to ensure companies on the programmes had the resources and capabilities to continue on those programmes and get the benefits from them. We also carried out a survey in April as the crisis hit. It showed that 80 per cent of businesses had seen a dramatic reduction in their sales in the first few weeks of the crisis.”

Adapting to help SMEs in a new landscape

InterTradeIreland then widened its approach, introducing a number of new supports to help businesses that trade across the border move out of crisis mode and into the recovery phase. At this point Gough stresses that the body wanted to develop initiatives that focused on its remit of cross-border trade and business development, and not to confuse the landscape for SMEs by duplicating what other government agencies were doing in both jurisdictions. He acknowledges the comprehensive response from both governments to support businesses on both sides of the border.

“Our approach has always been value through collaboration. We had worked previously with TechIreland, an organisation that identifies and works with new emerging technology companies across the island, to develop a Covid-19 business map. This showed all the businesses that were willing to cooperate in response to a public need related to the pandemic,” explains Gough. The business map was launched in April 2020 and has since grown substantially. The initiative has led to cooperation between companies on several projects. “The map shows a business other potential business partners and effectively speeds up the collaboration process. Businesses have been incredible in the way they have responded in repurposing production to meet a public need,” he adds.

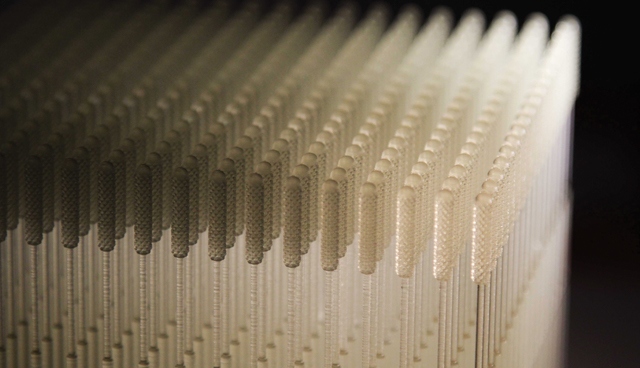

InterTradeIreland’s existing programmes have also been leveraged to respond to the crisis. The Co-Innovate programme aims to increase the numbers of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) involved in research and innovation across the border region of the Republic, Northern Ireland and parts of western Scotland. The five-year €16.6 million project was the first funding offer to be announced under the EU’s INTERREG VA Programme, managed by the Special EU Programmes Body. In the wake of the pandemic, the programme brought together, and provided the initial funding for a partnership of 20 businesses supported by Queen’s University Belfast to mass produce visors on an industrial scale of tens-of-thousands each week. “This existing programme showed that businesses are willing and capable of re-sponding on a cross-border basis,” says Gough.

Going digital

InterTradeIreland’s corporate plan has digitalisation both of its own supports and helping SMEs to adapt and adopt digital processes, as one of its central planks. The Covid-19 pandemic has brought forward the digitalisation of business processes, forcing change and adaptation in a time frame that no one expected. As a result, the body has been able to respond very quickly to business needs and has re-engineered many of its services, including its sales programmes, funding supports and new Covid-19 initiatives so that they can be accessed and implemented in the new environment created by the pandemic.

It also launched the E-Merge programme to help companies embrace their digital sales options. E-Merge provides £2,500/€2,800 fully funded consultancy support to help businesses develop online sales and e-commerce solutions. Advice is provided in a range of areas including e-marketing, website management, e-commerce, online payment systems, secure logistics, customer service and the legal and insurance implications of moving online. There has been a strong uptake for the programme as the Covid-19 crisis has hastily forced many businesses online.

There’s also been a lot of interest in InterTradeIreland’s Emergency Business Solutions programme. Firms are offered £2,000 /€2,250 worth of support to risk asses their current business position, assist with cash flow forecasting, HR issues and to help manage suppliers. Businesses are also directed to the appropriate source of relevant supports in Northern Ireland and the Republic.

|

Hero Shield Project, Shnuggle A group of firms set up not-for-profit company, Hero Shield Ltd, to manufacture face visors for health workers with help from €300,000 of funding from the Co-Innovate programme. The Co-Innovate initiative, led by InterTradeIreland and supported by the European Union’s INTERREG VA Programme, managed by the Special EU Programmes Body (SEUPB), is providing the cash injection to the cross-border group of 18 companies, to help them produce thousands of low-cost, quality face shields in response to Covid-19. There has been an overwhelming response from the health sector both north and south, with Health and Social Care Northern Ireland having placed an order for 70,000 visors per week. Adam Murphy, CEO of Shnuggle, said: “Hero Shield was born when we heard about the desperate need for PPE. We saw an opportunity to use our collective skills and knowledge of precision engineering, plastics and manufacturing to create a low-cost, fast-manufacture face shield. We wanted these to be distributed free of charge or at cost. We will sell some product at a small profit to private companies, which will raise funds to make even more Hero Shields, allowing us to continue operating as a not-for-profit company. Funding from Co-Innovate has provided us with the financial support to keep this amazing venture running for the benefit of all in society.” |

Another element that illustrates InterTradeIreland’s willingness to adapt to the new landscape is the reconfiguration of its all-island Innovation programme that brings in internationally recognised speakers. The programme is now delivered online and is reaching an even wider audience than previously. A series of funding and recovery webinars that help businesses navigate their way through the current crisis as well as avail of key supports in both Northern Ireland and the Republic, has also proved popular.

Looking ahead, Gough sees the area of supply chains becoming more important: “We are going to have to help firms take a strategic look at their supply chains. There is an obvious need to diversify supply chains and even to bring them closer to home. Redesigning supply chains will be an important factor in the recovery and we are looking at initiatives in this area.”

Brexit

Brexit is another once in a generation issue and it will again come into sharp focus towards the end of 2020, with the issue of deal or no deal. “Although there is the Northern Ireland protocol, there are still important issues that could impact on the way we trade across the border on this island. One of the main issues is the significant amount of cross-border trade from Northern Ireland to the Republic that ultimately leaves the island as part of an EU free trade agreement,” says Gough. If Northern Irish goods are not treated as part of the EU, that could have real consequences for trade from north to south.

|

Seedcorn, Tracworx This Limerick company was last year’s winner of InterTradeIreland’s Seedcorn competition, which recognises and identifies early start companies with high potential. Tracworx has used the Seedcorn funding to repurpose its technology to combat Covid-19. It has developed a tracking device to help hospitals with social distancing and to trace where contacts have been indoors. |

Challenges and opportunities

The main challenges to the end of 2020 will be the emergence from the Covid-19 crisis and Brexit. Businesses will redesign and adapt as we move to a new ‘normal’ but Brexit will also be a challenge. “We are planning for the recovery and to help business who trade across the border to repurpose and redesign their business models and to keep them informed and ready to react to whatever Brexit deal emerges,” Gough states.

Before Covid-19, InterTradeIreland had looked at major areas of opportunity for cross-border trade and business development. “Some of these will become even more important in light of the current crisis. These include Industry 4.0 and a raft of new technologies, such as blockchain and AI that will change the way we do business. There are opportunities for early adapters of these game changing technologies. Other areas where there are real opportunities for cross-border cooperation include adaptation to the low carbon economy, cooperation to drive small firm productivity and in sectors such as advanced manufacturing and health and life sciences – where there is scope for developing internationally competitive all-island clusters building on world leading indigenous businesses, multi-nationals and world class R&D.

“While the short term is focused on recovery from the current crisis and InterTradeIreland has been very quick to respond, looking further ahead there are many real opportunities for cross-border cooperation that will deliver mutual benefits in terms of business development and international competitiveness,” he concludes.

Included are three examples of how InterTradeIreland has been helping business collaborate, pivot and respond Covid-19.

|

CovidBizMap, Axial3D InterTradeIreland teamed up with TechIreland to develop an interactive map. It tracks those responding to the needs of the Irish Government and Northern Ireland Executive during the Covid-19 pandemic. It is generating new connections and collaborations and identifying clusters of expertise. One Belfast company on the map is Axial3D, a former winner of an InterTradeIreland FUSION Exemplar award. At the core of this innovative SME is 3D printing capability. The company is now printing thousands of face shields and test swabs for Covid-19. |

W: www.intertradeireland.com

InterTradeIreland helps SMEs across the island by offering practical cross-border business funding, intelligence and contacts.