All in this together? Post-pandemic economy

As a result of Covid-19 and the subsequent lockdown, Ireland faces the largest recession in its history. Austerity measures are likely to hinder the post-pandemic recovery, the Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) has warned.

Ireland, like most countries, is now experiencing a significant economic downturn as a consequence of the lockdown measures necessitated by Covid-19 and initiated in March 2020. The extraordinary decline across Europe is unlike anything witnessed before.

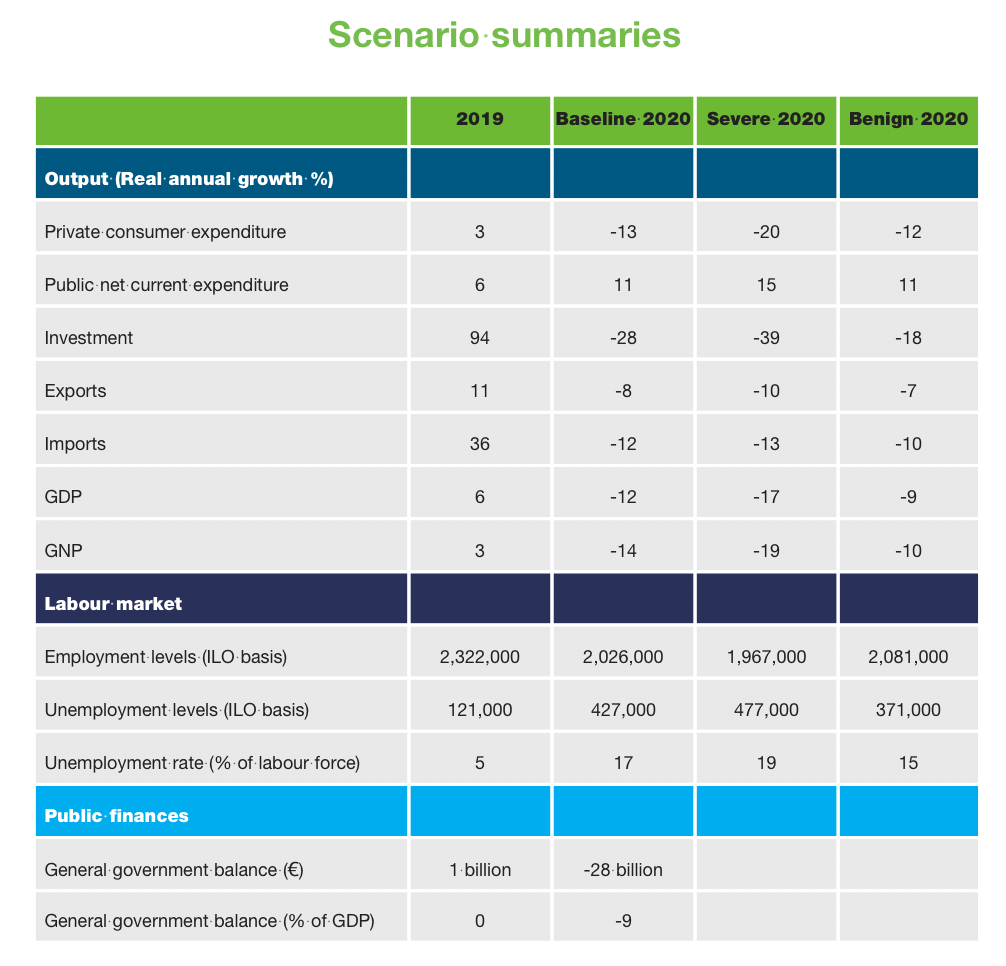

Assessing the post-Covid-19 prospects of the Irish economy, the ESRI’s Summer Quarterly Economic Commentary provides three different scenarios.

1. Baseline: New normal with ongoing physical distancing

Following the Government’s roadmap for easing the lockdown, the baseline scenario is considered the most likely to occur. From August onwards, the economy will begin to recover but with continued social distancing measures, will still operate below pre-pandemic levels. The baseline scenario projects a 12.4 per cent decrease in real GDP in 2020.

2. Severe: Second wave requiring strict lockdown

A worst-case projection, the severe scenario anticipates a second wave of Covid-19 in Q4. In this scenario, real GDP will decline by 17.1 per cent and unemployment will peak at 19 per cent for the year.

3. Benign: Successful disease suppression

In the best-case or benign scenario & Covid-19 is successfully suppressed and economic normality restored in Q4. However, real GDP will still fall by 8.6 per cent in this scenario and unemployment levels hit 15 per cent for 2020.

Therefore, regardless of the scenario, the Irish economy is projected to experience the most significant annual decline in its history. Declining consumption means that the economy will be comprehensively impacted. In the baseline scenario, investment and consumer spending are expected to drop by almost one-third (28 per cent) and 13 per cent respectively. Based on reduced consumption, imports are assumed to decline by 12 per cent, while the global downturn is expected to reduce the external demand for Irish exports by over 8 per cent.

Already in the labour market there are obvious indications of the pandemic’s impact. Comparing figures for Q4 2019 with those for people claiming the Government’s Pandemic Unemployment Payment (PUP), the ESRI illustrates the demographic and geographic analysis of the unemployment surge.

Unemployment spiked to a record 28 per cent in April, with young people bearing the brunt. “Claims for the [Pandemic Unemployment] Payment amongst younger workers represent a far greater share of employment than for other age categories,” the Summer Quarterly Economic Commentary states.

Almost 60 per cent (27,000) of 18 to 19-year-old workers who had a job last year are claiming the payment, while over 47 per cent (93,000) of 19 to 22-year-olds who were employed are doing likewise.

Geographically, regions outside Dublin are the worst affected. In the border region, almost 30 per cent (51,586) of the workforce is claiming the payment, followed by 28 per cent (52,211) in the south-east and 26.5 per cent (54,823) in the mid-west. However, in Dublin alone, 171,874 people (over 24 per cent of the labour force) are claiming the payment.

As the lockdown eases, this upward trend in unemployment will revert to some extent, thought the baseline scenario still envisages unemployment exceeding 17 per cent for 2020.

Public finances have also been visibly affected with a public expenditure increasing to unparalleled levels while being compounded by a decreased economic activity and a resulting dip in revenue. The baseline scenario predicts a significant public deficit of €27 billion (9 per cent of GDP) in 2020.

Fiscal adjustment

In the coming months, as the financing of such a deficit will necessitate great attention, difficult decisions must be made. Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil have suggested that the incoming government must commit to a programme of deficit reduction.

However, the ESRI has warned against a knee-jerk response to the growing deficit. Instead, it advocates a stimulus package to boost recovery, followed by adjustments later in the new government’s lifetime.

Ahead of the publication of the Quarterly Economic Commentary for Summer 2020, ESRI Senior Research Officer Conor O’Toole and ESRI Research Professor Kieran McQuinn presented an overview of the document to the media.

“We have to focus on stabilising the economy, managing income supports and reigniting economic activity in the short- to medium-term,” McQuinn asserted.

Acknowledging that “some sort of fiscal adjustment” will be required, he emphasised that if the stabilisation is well managed, “that will ultimately minimise the scale of adjustment that’s needed over the longer term”.

There is a risk that moving to address the budget deficit too soon will inadvertently exacerabate the economic shock, necessitating an even larger adjustment in the long-term.

Potential consumer boom

In relation to personal savings, John FitzGerald’s contribution to the Quarterly Economic Commentary indicates that in contrast to the most recent financial crisis between 2008 and 2012, households in Ireland and beyond are likely to have a stronger balance sheet at the end of 2020 than at the beginning.

“It is widely recognised that consumers take into account both current income and expectations of future income when choosing their current consumption. Consumers are also affected by uncertainty about their future income, so that they may save to prepare for future shocks. Thus, it is no surprise that consumers today are engaging in precautionary saving in case of permanent job loss.

“In this crisis consumers are also unable to buy certain goods and services, such as foreign travel and the services of pubs or restaurants. Finally, consumers with financial assets may also be facing losses in the value of those assets, which may lead them to increase their savings today. Understanding which of these factors is causing the rise in saving in the current crisis is important,” FitzGerald writes.

The exceptional savings this year could have a significant impact on the economic recovery. While uncertainty may postpone a consumer boom, if household behaviour is similar to the last occasion of ‘forced’ saving, World War Two, it could contribute to “a more vigorous recovery than might otherwise be anticipated”, reducing the need for further fiscal adjustment.

However, FitzGerald concedes that even such a scenario “would go nowhere near compensating for the huge loss of output in 2020”.