Sustainability in action at Gas Networks Ireland

As the operator of Ireland’s €2.7 billion, 14,664km national gas network, which is considered one of the safest and most modern renewables-ready gas networks in the world, Gas Networks Ireland is ever mindful of its sustainability responsibilities and aims to contribute to the protection of the environment, while supporting the social and economic development of the communities where it operates.

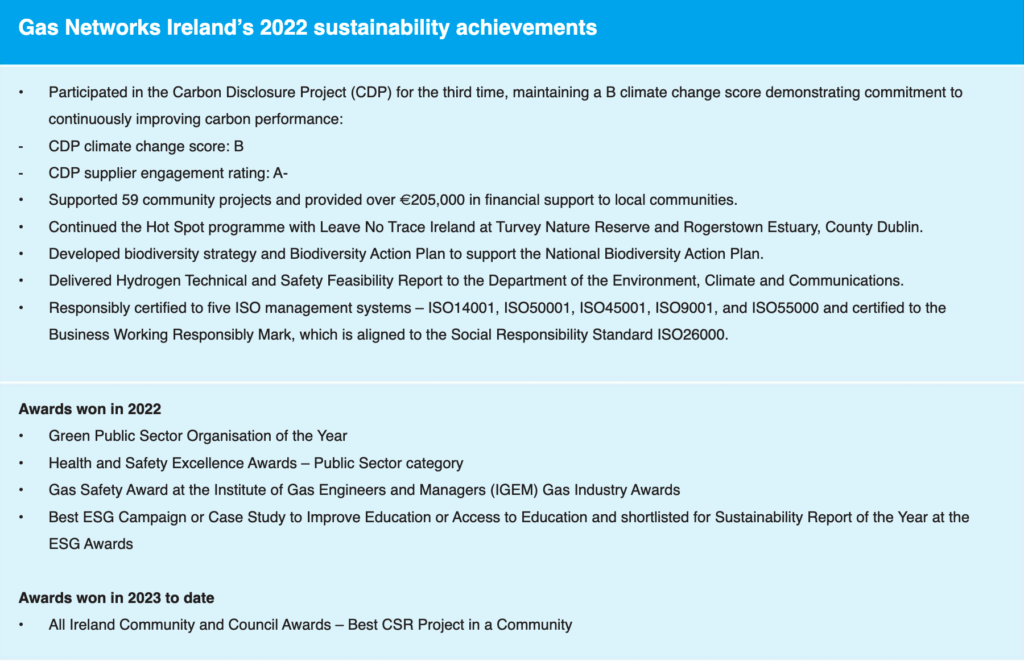

2022 sustainability report

Entitled Sustainability in Action and aligned to the Global Reporting Initiative standard as well as the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, Gas Networks Ireland’s fifth annual sustainability report, highlights the ongoing progress made by the national gas network operator in supporting environmental, social, and economic sustainability within both its own business and the communities in which it operates.

Valuable national asset

Ireland’s gas network is a valuable national asset which is playing a major role in achieving a clean energy future in the least disruptive way. While the utility’s principal activity is the transportation of natural and renewable gas on behalf of over 720,000 business and residential gas customers regardless of which gas supply companies they choose, the organisation attaches great importance to ensuring that its investment policies are aligned to the national strategic outcomes outlined in the National Development Plan 2021-2030, the Climate Action Plan 2023 and the Government’s wider energy policy.

The gas network is the ideal partner for renewable energies such as wind and solar. The large energy storage capability and flexibility of the network mean it can ramp up to meet high heat demand during extreme cold periods, or it can provide extra fuel for power generation when the wind does not blow, or the sun does not shine.